For a small company, the strategic acquisition is the exit with the highest return. This path is available when there is something in your startup that is valuable. This asset would drive more value for the acquirer than the rest of the rickety "spacecraft" can enable in the market. A more prominent company will put a bigger lens on the asset to generate greater returns.

But this seldom means survival of the company as an operating entity. Bo Burlingham investigated companies that sold or transitioned ownership in his book Finish Big. He found three exit paths: generational transition, financial buyers, and strategic buyers.

The first option is to transition ownership down a generation. The founder retires while handing to employees, partners, or family. The company remains in the friendliest hands who want to keep the company traditions but has the lowest financial returns.

A second option is selling to a financial buyer. A financial buyer usually wants the business as a cash flow engine. They strip out inefficiencies, invest where it was lacking, and pump for cash. Burlingham found happiness to be a mixed bag. Financial buyers assure the seller of their intent to protect the business, but they will do what they have to, and that which was precious to your idea of company culture may or may not survive. They do involve more significant financial paydays for the seller.

The third option is a strategic acquisition. As noted, this has the highest financial rewards. The cash flows do not drive the sale price. If your business is small, the cash flows would be smaller, meaning any reasonable financial sale has a lower ceiling. But a strategic acquisition could be massive because they do not care about your cash flow, only your asset.

At the same time, Burlingham found that many business owners were sad at the end of a strategic sale. They got an enormous pile of cash but watched their business get ripped apart or just shut down after extracting the secret sauce. They had an emotional stake in their companies and viewed this outcome with regret. Were the years building that venture and earning the trust of customers and employees wasted?

The question I ask is, how can we be happy with this outcome? As a technologist, I want to find solutions to problems. The business is a wrapper around that solution to monetize it. I am thrilled with a more prominent or wealthy enterprise putting my ideas to work. My (small) exits have had that quality. Why do others not feel this way?

In the realm of gray commerce, a "chop shop" is an enterprise that finds the most valuable parts of machines and extracts them for resale or transplant. The fencing technique is simple: steal the car, take the high-value components, dump the rest. There is good money in this approach, and one can remove the grand theft auto associated with the term and still find a lot of value.

This idea of "finding what's good" even applies to space travel.

In Apollo 13, Ed Harris's character marshals his group around a single question: "what do we have on this spacecraft that's good?"

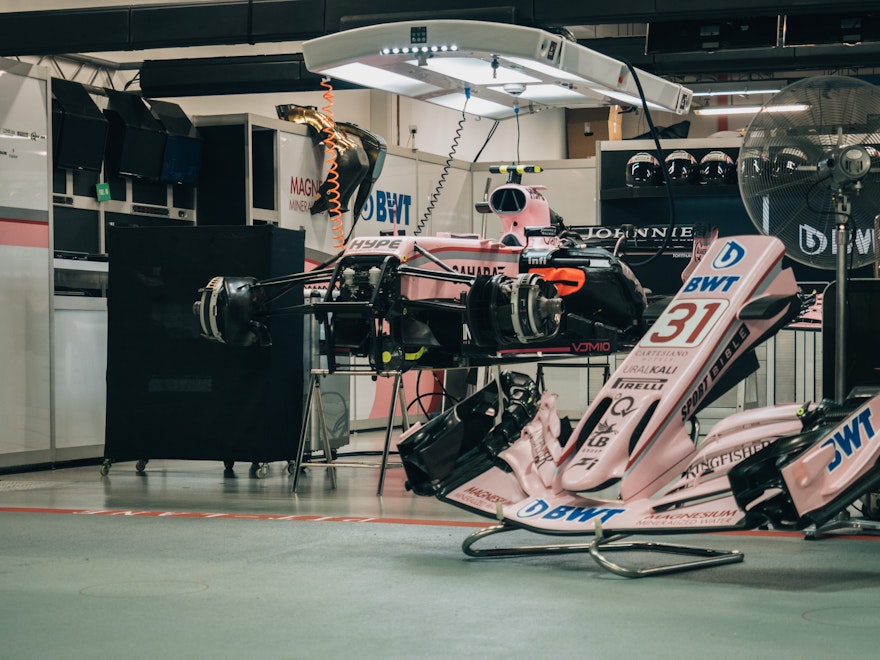

Finding "what's good" requires one to understand what "good" is. I am partial to Formula 1. In F1, the chop shop is the team garage. The mechanical crew always takes the vehicle apart, finding that which makes it go fast and removes everything else. The team asks three questions: what makes it accelerate, what lets it brake quickly, and what keeps it on the road? Everything else goes. The mission is to find that differentiator that will get a shorter lap time. This differentiator is not always as obvious or central as the engine. A decade ago, an innovative shape for an exhaust diffuser took a startup team - not even sponsored by a car company - to a dominant championship.

Another problem arises because many entrepreneurs have bound up the monetization structure, staffing, and culture with the original invention. Companies and ideas evolve simultaneously. Where does one end and the other begin? Growing a company can feel like managing a child rather than rebuilding a machine. Especially when the model starts to involve staff - people cannot be treated as machine parts!

So between not knowing "what's good" and having a problem separating the parts of the business, getting to the core of what is most valuable within the enterprise is work. How can we make this simpler? The siren song of lagging indicators comes to the fore. We hear recurring revenue is valuable, so that becomes the metric to which we manage.

And profitable revenue is an excellent metric for managing a business! Let's see how fast the car goes! We can focus on moving upward. We create jobs by adding staff and work hard to make the business work. That is all virtuous, right?

This path leads to the emotional reaction of the founders from Burlingham's book. The businesses built on this north star can be good - perhaps even great. But they will bury their strategic value. They will be surprised when they receive strategic offers and be disappointed when the creations they value - the wrappers for these assets - are torn asunder.

What is the answer? Embrace the mentality of the chop shop. Find what is good and surface it. Intentionally build the business around it to validate its value, and then look for the highest-value monetization opportunity. This latter is very likely to be the acquisition—plan for this outcome. One starts a flywheel: research project, followed by startup business with positive cash flow, followed by a strategic sale.

Photo by Goh Rhy Yan on Unsplash